Child migrants often miss months or even years of schooling. This hurts their chances of escaping poverty and having safer futures.

Ciudad Juárez is a large city in Mexico, along the country’s border with the United States. For thousands of migrants and their children, it is the last stop before they enter the U.S.

In Juárez, they wait for that chance to cross the border. U.S. policies make some people wait in Mexico for their court hearings to seek asylum.

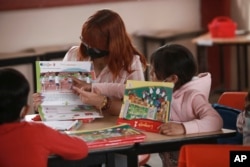

A number of Christian-based shelters in Juárez work to serve the urgent needs of this population, including education of school-aged children. The shelters have partnered with local schools in the effort.

The curriculum is not religious. But a strong belief in the good of education drives the programs. Teachers believe education will help the children socialize and find jobs wherever they find a permanent home.

Teresa Almada runs Casa Kolping through an organization supported by the Catholic Church. She said the migrant students get included “in the educational system so they can keep gaining confidence.” She added: “It’s also important … that the families feel they’re not in hostile territory.”

Victor Rodas is a 12-year-old student. His 22-year-old sister and guardian, Katherine, led him and two other siblings out of Honduras. The family fled after receiving death threats from organized crime groups. In Juárez, Katherine and her husband will not leave the safety of the shelter. But, she praised its educational program, which provides bus transportation so her siblings can attend Casa Kolping.

“They say the teacher always takes good care of them, plays with them,” Rodas said. “They feel safe there.”

Many housed in their shelter fled from Central America. Growing numbers of Mexican families fleeing illegal drug trafficking groups are arriving too.

For a while after the school program started in October, teachers asked parents to join their children in their classrooms to build trust. Among them was Lucia, a single mother of three children. She fled the Mexican state of Michoacan after drug traffickers “took over the harvest and everything” in their home. She asked to be identified by just her first name for safety.

“Education is important so that they can develop as people and they’ll be able to defend themselves from whatever life will put before them,” Lucia said. She and her family have been living there for nine months.

More than 30 children from the Christian-based shelters around Ciudad Juárez attend Casa Kolping. First to third graders gather in one classroom. Fourth to sixth graders meet in another.

In the U.S. Victor hopes schools will be “big, well-cared for," and will help him reach his goal of becoming a building designer.

“If you ask the kids, their biggest dream is to cross to the United States,” said teacher Yolanda Garcia.

Many parents do not want to send their children to school in Mexico, where they do not plan to stay. Also, many public educators do not want to bring in migrant students. There is a fear of losing teachers if class sizes decrease when students leave suddenly, said Dora Espinoza. She is a school official in Ciudad Juárez.

In addition to uncertainty, poverty and discrimination keep nearly half of refugee children from school worldwide, says the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR.

But the biggest barrier is insecurity. Threatened with violence by gangs both in their hometowns and along the trip to the U.S., many parents are afraid to leave their children alone. The shelters address that by providing secure transportation for the children.

The migrant children have experienced a lot of trauma, educators say.

Samuel Jimenéz is a teacher at one of the schools. He said students will tell him they are there “’because they murdered my parents. ’ They tell it in detail, children don’t cover anything up.” But, Jimenéz said, “the moment they’re here, we can take them out of that reality. They forget it.”

Other students arrive unable to read or write.

“We are faced with all kinds of falling behind,” said Garcia at Casa Kolping. “But most of all, with a lot of desire to learn. They missed school. When you give them their notebooks, the emotion on their face … some even tell you, ‘How lovely it feels to learn.’”

I’m Dan Novak. And I'm Ashley Thompson.

Dan Novak adapted this story for VOA Learning English based on reporting by The Associated Press.

____________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

curriculum — n. the courses that are taught by a school, college, etc.

confidence — n. a feeling or belief that you can do something well or succeed at something

address — v. to give attention to ; to deal with

trauma — n. a very difficult or unpleasant experience that causes someone to have mental or emotional problems usually for a long time