VOA Learning English presents America’s Presidents.

Today we are not going to talk about any one president. We will instead talk about the presidency itself -- what some people call “the office of the presidency.”

That does not mean the room where the leader of the United States works. Here, it means the position and powers of the U.S. president.

Sidney Milkis is part of the Miller Center of Public Affairs at the University of Virginia. He and others at the Miller Center are specialists on U.S. political history.

Milkis says that, when it was created in the late 1700s, the U.S. presidency was unlike any other position in world history.

“For thousands of years before the American Constitution people thought a strong executive power and a democracy – what Jefferson called self-government – were incompatible. Because how could a sovereign people delegate tremendous responsibility to one individual and still consider themself a democracy, even a representative democracy?”

In other words, the idea of giving a lot of power to one person made sense – if the country were a monarchy and ruled by a king or queen.

And giving a lot of power to an elected group in a legislature made sense – if the country were a democracy, and voters elected representatives.

But giving a lot of power to one person in a democracy did not seem to make sense.

The writers of the Constitution understood this situation. They were concerned about giving one person too much power. Remember, the country’s founders had just fought a war for independence against the British. The American colonists had not liked being under the control of a British king.

They also worried that a strong executive could become a tyrant or corrupt, adds curator Harry Rubenstein. He is a curator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

But the Constitution’s writers had also seen the problems of a weak executive branch. Asking state legislatures to make national decisions took too long, and sometimes the problems were never resolved at all.

Historian Sidney Milkis says that, as a result of these ideas -- some of them conflicting -- the writers of the Constitution argued about what the office of the president should be.

“There were people like James Madison and [Thomas] Jefferson, who thought the president’s power should be limited, and the term ‘president’ meant ‘preside.’ And Congress and the states should be the leading venues of American democracy.”

Other people who helped write the U.S. Constitution, such as Alexander Hamilton, thought the president should be what Milkis calls “the anchor of American democracy.” Hamilton thought the president should have enough power to direct large projects for the public good.

So what happened?

Well, in 1787, delegates to the Constitutional Convention found a unique solution. First, they agreed to make the president a one-person job. One person, they reasoned, could both make decisions more effectively than a group, and be more easily held responsible for them.

But they decided not to give the president too much power. The person would be elected for one four-year term at a time. And the president would share power with a national legislature and a supreme court.

The delegates also decided some of the details about how the president would be elected, and how to remove the person from office. And they said the president would have a number of duties. They include being the commander in chief of the military, nominating public officials, and giving Congress a report on the state of the Union. This list is comes from Article II of the U.S. Constitution.

But a lot of the job description was left open. It said the president “shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”

Since it was written in 1787, that expression has informed discussions about what powers the U.S. president should really have.

Historian Sidney Milkis says Americans are still debating how much power the president should have. For most of the 19th century, he says, the powers of the president were more limited. But since the 20th century, the position has become more powerful. The president has moved closer to the center of American democracy.

But in time, Milkis says, Americans may decide to limit the president’s authority again, and give more power to Congress and state governments.

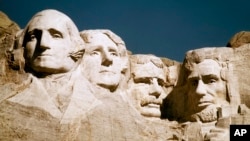

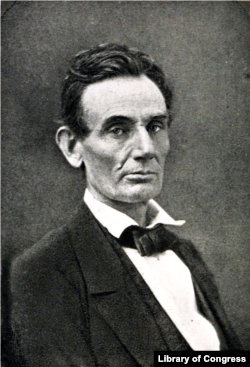

Milkis adds one more thing about the unusual invention of the U.S. president. It was unclear that the public would trust a national executive. But as our America’s Presidents series shows, for the most part, Americans respect the office of the president. Instead of fearing our great leaders, says Milkis, we honor them.

I’m Kelly Jean Kelly.

Kelly Jean Kelly wrote this story for Learning English. George Grow was the editor.

_____________________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

incompatible - adj. not able to exist together without trouble or conflict : not going together well

sovereign - adj. having independent authority and the right to govern itself

preside - v. to be in charge of something

venue - n. the place where an event takes place

anchor - n. a person or thing that provides strength and support

unique - n. belonging to or connected with only one particular thing, place, or person